The puriri moth, Aenetus virescens, is a moth of the family Hepialidae, endemic to the North Island of New Zealand. It is New Zealand’s largest moth, with a wingspan of up to 150 mm.[1][2]

The moth spends the first five to six years of its life as a grub in a tree trunk (including non-native species such as Eucalyptus), with the last 48 hours of its life as a moth. Footage has been taken of a puriri moth chrysalis hatching over a period of one hour and forty minutes.[3]

A lifecycle that ends with no mouth

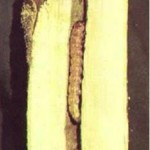

Fig. 1 - A "7-shaped" tunnel made in a stem of Carpodetus serratus (putaputaweta) by a caterpillar of the puriri moth. Length of the tunnel is 120 mm; length of the caterpillar is 58 mm.

The life cycle is not fully known, but probably occupies at least 7 years. The first three caterpillar stages attack the thin bark of regeneration trees. They shelter beneath a tent made of silk, bark-scrapings, and frass, often sited at a twig base. The third-stage caterpillars tunnel into small-diameter branches and, as they increase in size, may leave their old holes and attack larger- diameter material. The tunnels are typically 7-shaped but frequently there are extra vertical shafts (Fig. 4), presumably occupied by the caterpillar when it was smaller in size. The caterpillar rests in the vertical shaft, but ascends to feed on living callus tissue at the entrance. The tunnel slopes up from the entrance, presumably preventing the entry of rainwater. The opening is covered with a tough, fibrous, silken web, which so well camouflages the holes (Fig. 5) that they are often

difficult to detect.

Vel nisi, porttitor placerat nec et natoque et, pulvinar turpis augue, facilisis in. A. Mattis porttitor, phasellus. Ac lectus sit parturient tempor dapibus dictumst turpis purus magnis tincidunt diam nec pid magna.

Robert Hoare

Related Activities at the House

Citizen Science – Butterfly Tagging

Ever wonder where Monarch butterflies go for the winter? The Monarch Butterfly New Zealand Trust is looking for ‘citizen scientists’ throughout the country to report sightings as the Monarchs follow their annual migration. A degree is not needed; anyone can take part, and everyone, schools included, are welcome to join the Trust’s annual project. Secretary Jacqui Knight says if we are to conserve species effectively, it is vital we monitor how they are faring.

“The status of our flora and fauna depends on the effects of climate change, pollution, alien species and land management,” she said. “We need to know more about our insects to predict the impacts of such change, and to develop an appropriate response.”

“By tagging and following Monarchs, we can use them as indicators of the status of our environment here in NZ,” said Dr Mark Hauber, who works in the field of Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour at the University of Auckland’s Biological Sciences.

“Tagging serves a dual purpose,” he says. “Not simply by collecting critical data, but also by introducing people to the method and purpose of scientific investigation.”

The butterflies typically form large clusters, sometimes containing hundreds or thousands of butterflies, on trees in well-sheltered areas during the colder winter months.

- Butterfly transects

- Butterfly tagging

Pellentesque habitasse nisi vut ridiculus? Nec. Eu habitasse! Tortor lorem, dignissim quis turpis tortor augue, nisi! Ut lacus, elementum adipiscing vel eu. Lacus pulvinar augue sed ac odio turpis? Placerat tempor porttitor sit arcu dolor sagittis hac? Elementum, phasellus a aenean et, integer sed tempor aliquet integer enim purus mattis, turpis placerat! Quis turpis.

Related Art Projects – The Pollinator Frocks

The Pollinator Frocks Project is a limited edition collection of surface pattern designs and clothing based on scanning electron microscopy images of plant pollen grains linked to endangered pollinators. These digitally enhanced images form the basis for a range of striking and unusual printed fabrics, which act as ‘wearable gardens’.

The collection was tested in New Zealand’s Pukekura Botanic Parklands as part of the art, technology and ecology event SCANZ 2011: Eco sapiens.