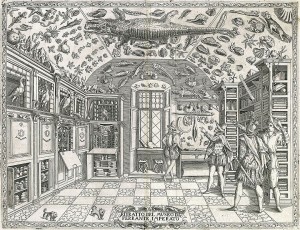

A sense of wonder has long been seen as a catalyst to the imagination, to creativity and to understanding. Fifth and Sixteenth Century ‘Wunderkammers’ or ‘Cabinets of Curiosity’ were rooms of encyclopaedic collections set aside for the sole purpose of inciting wonder. Regarded as a microcosm of the theater of the world, they held exotic clues to fabulous animals yet unseen, man-made things wondrously fine or small, ethnographic evidence from distant lands.

A famous seventeenth century cabinet holder Althanius Kircher, was (among many things) one of the first to see microbes through a microscope, and was an inspiration for the intriguing Museum of Jurassic Technologies curated by David Wilson. Claiming 6,000 visitors a year, the popularity of ‘wonder’ is still apparent. Similarly the blog site BoingBoing – ‘A Directory of Wonderful Things’ – which focuses on ‘cyberpunk, steampunk, counter cultures, gadgets, hacking and futuristic memes’, is currently one of the world’s most popular blogs[1].

Wunderkammer and New Worlds

Fold-out engraving from Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’Historia Naturale (Naples 1599), the earliest illustration of a natural history cabinet

The Age of the Enlightenment in Europe, which coincided with the popularity of Wunderkammer collections, was an age of discovering the ‘New World’ across the seas. Strange and wondrous items were collected for their examination and classification, developing taxonomies [Linneaus] of understanding we still use today. Discussions were held in these spaces with astronomers, philosophers, theologists, etc – those learned in the arts and sciences. It was at this time common for learned people to be a polymathic – highly knowledgeable in many areas – rather than the specialization that is the norm of today.

With knowledge disciplines now so separated, might their overlap once again ‘make strange’ everyday natural elements and inspire their re-assessment? Might this also be aided by the further complication of intercultural comparisons? In this way, might a contemporary wunderkammer be evoked, through the sharing of perceptions?

In philosophical terms, this state of mind has been discussed as thaumazein – a making strange of the everyday [Heidegger]. A difficult and often vulnerable state to sustain, the notion of ‘wonder’ has been relegated to the realm of the fanciful in modern society [Rubenstein]. Yet it is this reaching into the unknown that is often reported as being at the heart of new knowledge seeking and consequent discovery [From Galileo to Gell-Mann]. In addition, the interplay of art and science can be seen as a means for creating new questions for discovering new thinking [Malina].